For a long time, I understood art history entirely in relation to Belgian painter Rene Magritte. The Dadaists existed to lay the framework for Surrealism, the movement Magritte was a part of. Hieronymus Bosch was the early Netherlandish artist whose dreamlike figures might’ve inspired Magritte. Salvador Dalí was that other Surrealist whose work was kind of like Magritte’s…but not really. For all I cared, Renaissance artists only mastered perspective so that Magritte could come along and upend it.

I owe this oddly specific take on art history to a generic brand of suburban angst and a high school painting teacher with a penchant for spontaneously launching into lengthy art history lectures.

I first saw the work of Magritte in her classroom, on one of those grey, winter afternoons where time feels immovable. When she called me up to her desk, I was working on a new painting—a rudimentary expression of my nascent existential dread—depicting clocks with menacing, serpentine tails, spiraling into oblivion. My teacher pulled out a hardcover book on Magritte and

generously likened my work to Golconda, a 1953 painting of floating men multiplied ad infinitum, in a suburban horizon.

René Magritte. Time Transfixed , 1938. Joseph Winterbotham Collection. © 2018 C. Herscovici, London / Artists Rights Society

(ARS), New York..

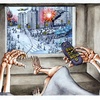

At first, the painting reminded me of The Rapture, if the only people being saved were European businessmen; or an illustration of the 1983 song “It’s Raining Men.” But in Golconda, there is no indication of motion. Wearing bowler hats, suits, and apathetic expressions, the figures float, weightless, like specters.

The grid-like composition of the figures reminded me of the insistent order in my daily environment. I thought of the trees plotted along manicured lawns with a meticulous uniformity that, soon after seeing this image, would seem as laughably absurd as the floating men. Golconda does what Magritte does best: takes something ostensibly self-evident and renders it distant, mysterious, sometimes humorous. Here, it was an archetype I was all too familiar with—the male breadwinner, the suburban patriarch—made almost goofy.

My obsession with Magritte arose, fortuitously, around the same time my mom went to work at an airline, offering me the opportunity to travel anywhere at virtually no cost. Taken by these strange floating men, I ventured from Buffalo to Brussels and back, chasing down Magritte paintings I had only ever seen in books.

The False Mirror (Le Faux Miroir)

René Magritte

There was La Voix des airs (The Voice of Space) (1928), at my hometown art museum the Albright-Knox, where Magritte transformed horse bells into imposing, alien forms. Then, there was Time Transfixed (1938) at the Art Institute of Chicago, where Magritte interrupts the quietude of a living room with a steam engine train. At the Tate Modern in London, I saw Man With a Newspaper (1928). In it, four panels depict the same room from slightly differing perspectives—creating the sense that something is “off” but never quite allowing you to pinpoint why.

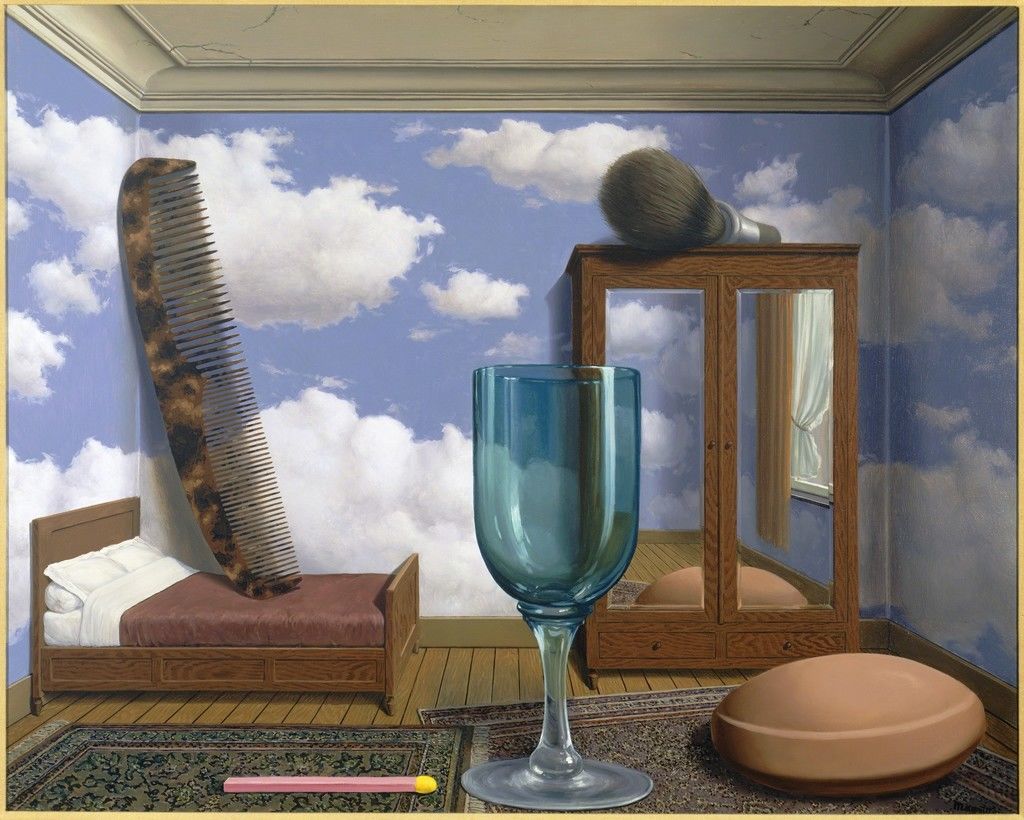

In the same way that after reading fiction, the voice in your head might take on the tendencies of a strong narrator, Magritte’s quirks became a filter for my reality. His Empire of Light (1953–54) filled the shifting dusk light in my hometown with drama. Personal Values (1952) brought renewed attention to the ephemera of daily life: a comb, makeup brush, and the performances they all imply.

Looking at Magritte’s Golconda, you take on the perspective of the figures, suspended in the midday light. I would think of Golconda while shuffling into a church service at my school auditorium or being herded around in uniform with my swim team—my selfhood dissolved into mass spiritual or athletic ritual. Later, Golconda would visit me as I filed onto a crowded escalator in Penn Station at rush hour. The image returned as I peeked over the divider of a cubicle to see endless rows of corporate enclaves around me.

Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values)

René Magritte

Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values), 1952

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)

At some point, I came around to an art history with reference points and narratives that did not include my good old Surrealist friend. I studied art history in college, which I got into, in part, by writing several admissions essays about Magritte. And, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say my current work in arts journalism is a direct result of that strange, resonating image of airborne, well-dressed men.

But it was not all revelations. As I traveled, I found that the more extraordinary the measures I took to see Magritte’s work, the more ordinary Magritte himself seemed. On one particularly ambitious weekend, I visited the Magritte retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and then flew to the Magritte Museum in Brussels the next day. On that short trip, Magritte “the artist” became Magritte “the suburbanite.” He became Magritte who wore bowler hats, forged artworks, and never had quite enough money. He became the Magritte who was subject to the same banal reality as me—but rather than dreading it, he was intoxicated by it.

Kelsey Ables

Sep 25, 2019 8:18am